In the introduction to his story collection Skeleton Crew (1985), Stephen King remarks that “Reading a good long novel is in many ways like having a long and satisfying affair” (a few lines later he amends it to “an affair or a marriage”), while “a short story is like a quick kiss in the dark from a stranger.”

A novella would seem to land somewhere in between, the equivalent of that dude you spent the weekend with at that cool music festival out in the desert, or of a summer-camp romance, or–if the book isn’t good–of an ill-advised fling with a close friend. I especially like it when novelists who are known for writing huge books flip the script on us and bring out something much trimmer. For example, there’s Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day; Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49; and Dickens’s Hard Times (short for him, anyway). On the nonfiction side, there is William Styron’s Darkness Visible.

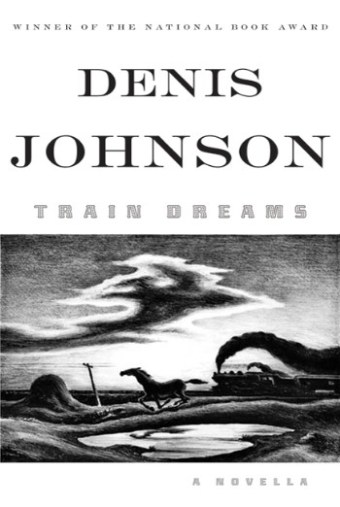

Denis Johnson has written more than one solid short novel–The Name of the World (2000) and Nobody Move (2009) are both fantastic–but the bulk of his popular rep is based on 2007’s Tree of Smoke, the Vietnam War behemoth that won a National Book Award. Literate people know it even if they haven’t read it. There’s also his hugely underrated NorCal narco-Gothic thriller, Already Dead (1998), which a lot of lazy critics griped was overwritten and too slow. (It isn’t either.)

In 2002 he published Train Dreams in The Paris Review, but the narrative wasn’t released as an independent book until a couple of years ago; a slim little thing that will fit in your coat pocket, it weighs in at 116 pages. You can read it during a cross-country flight. That’s what I did. No big deal, brah. Guess I’m just a reader.

Set in the American West (mainly Washington, Idaho, and Montana) during the first half of the twentieth century, the book’s central character is Robert Grainier, a laborer. Nothing much happens to him: he doesn’t invent anything or kill somebody or write a famous book. Grainier works a lot of rough jobs, gets married, gets widowed, works more jobs, and makes it into his eighties, dying alone in his cabin. He never even gets drunk or shoots a gun (strange, given where and when he lives), though he does see Elvis’s touring train once.

But Johnson’s gorgeous narration (a sustained brew of narrative-driven realism, Gothic tall-tale, and dilatory, lush, at times surreal prose poetry) underscores the astonishing density of an ordinary life, the kind that most of us have, whatever era we happen to inhabit. Here is Robert as a logger in northwest Washington around 1920:

He liked the grand size of things in the woods, the feeling of being lost and far away, and the sense he had that with so many trees as wardens, no danger could find him. . . . Cut off from anything else that might trouble them, the gang, numbering sometimes more than forty and never fewer than thirty-five men, fought the forest from sunrise until suppertime, felling and bucking the giant spruce into pieces of a barely manageable size, accomplishing labors, Grainier sometimes thought, tantamount to the pyramids, changing the face of the mountainsides, talking little, shouting their communications, living with the sticky feel of pitch in their beards, sweat washing the dust off their long johns and caking it in the creases of their necks and joints, the odor of pitch so thick it abraded their throats and stung their eyes, and even overlaid the stink of beasts and manure. At day’s end the gang slept nearly where they fell.

Just look at that rhythm. After the switchbacks of a multi-clause, carefully unspooled, image-heavy sentence comes a short one rendered even crisper by Johnson’s decision not to use a comma after the introductory phrase “At day’s end.”

This being a story with a third-person narrator, the usual question arises of where the main character’s cognition stops and the author’s discourse begins, but regardless of where you think the border zone is, Robert is an observant, sensitive man, alive to the shocks of his own life.

Johnson’s mystery narrator also relishes subsidiary characters. This is how the dynamite handler in the logging camp dies:

It looked certain that Arn Peeples would exit this world in a puff of smoke with a monstrous noise, but he went out quite differently, hit across the back of his head by a dead branch falling off a tall larch–the kind of snag called a ‘widowmaker’ with just this kind of misfortune in mind. The blow knocked him silly, but he soon came around and seemed fine, complaining only that his spine felt ‘”knotty amongst the knuckles” and “I want to walk suchways–crooked.” He had a number of dizzy spells and grew dreamy and forgetful over the course of the next few days, lay up all day Sunday racked with chills and fever, and on Monday morning was found in his bed deceased, with the covers up under his chin and “such a sight of comfort,” as the captain said, “that you’d just as soon not disturb him–just lower him down into a great long wide grave, bed and all.”

The prose is always like that, swinging between the straightforward (“deceased”) and the disorienting (“knotty amongst the knuckles”!). In short, Train Dreams is incredible. You can read it over a weekend. And it costs about $5 on Amazon. You can thank TGR later.